Research led by a University of Iowa student is opening new doors to potential uterine cancer treatments that could allow patients to regain their health while retaining their ability to have children, the university reported.

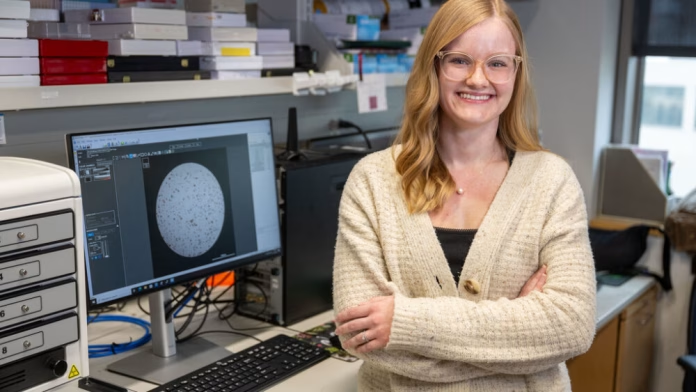

Katie Colling, a fourth-year doctoral candidate in the UI cancer biology program, has found promising results from testing different types of drugs aimed at balancing hormones in the uterus — called progestins — on cell cultures created from patient tumor tissue, according to a university news release.

Most uterine cancer cases are caught early, Colling said, and are treated with a surgery that removes the uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries. This leaves these patients without the ability to have children. Surgery isn’t always viable, however, for patients with other health factors or those planning to have children, and the current progestins used for uterine cancer treatment are not effective for everyone.

“The problem with these drugs is that they don’t work for every patient. So some patients respond well initially, but for up to 40% of them, their cancer actually comes back, and that’s not a good thing,” Colling said in an interview. “Currently, there are only three progestins used in the clinic, or three hormone therapies, yet over 20 are used for other purposes in women’s health, such as contraception, and we don’t understand which is most effective for treating uterine cancer.”

Uterine cancer is the fourth-most common cancer in women and the fifth-most common cause of cancer death in the U.S., Colling said, and it recently passed ovarian cancer to become the deadliest form of gynecologic cancer. According to the National Cancer Institute, the cancer’s five-year survival rate between 2016-2021 was just over 80%, and close to 14,000 people have died of uterine cancer in 2025.

Working in the lab of obstetrics and gynecology researcher and UI professor Kristina Thiel, Colling said she has spent the past two-and-a-half years testing different progestins on cell cultures from tumors called “organoids” to see how they impact tumor growth and cell death within it.

She called the results she’s seen so far “really promising.”

“I have compared a large panel of progestins to those that are currently being used in the clinic, and I have identified five that are performing better than those currently used to treat patients,” Colling said.

Colling’s work had a big hand in earning the UI, as well as the University of New Mexico, University of Utah and University of Kansas, a five-year, $12.8 million grant from the National Cancer Institute, Thiel said.

The University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center is the lead organization on the project, titled “Advancing Hormone Therapy for Endometrial Cancer” and awarded its funding in August, and the UI team will receive around $500,000 annually to continue with its work testing progestins.

“Some of the data that Katie generated were integral to us getting this funding from the National Cancer Institute,” Thiel said.

Next steps in Colling’s work include taking the top progestin candidates she’s identified and testing them in mice, with the data from that phase planned to be combined with data from other institutions and used for clinical trials.

Spreading awareness

Colling’s passion for her work is driven by both academic and personal reasons, she said. The student researcher said she first got interested in cancer-specific research during a summer internship at New York University, and it was during that same summer that she learned her grandmother’s breast cancer had returned after 15 years of remission and metastasized “practically everywhere.”

“From that point on, I kind of saw her navigate the challenges and toxicities associated with cancer treatment and that really inspired me to research safer and more effective therapies for cancer patients,” Colling said.

One question Colling said she’s asked herself is why, with so many progestin options available and being used for other means, they haven’t been tried for uterine cancer treatment. The current progestin treatments have been utilized since the 1970s, and she said women’s health has been traditionally under-researched. This is why she said she’s “really excited” to further this study and advance cancer treatment therapies.

Both Colling and Thiel emphasized that the public should be educated about their research, as well as signs of cancer developing and other information to keep them safe and healthy. Colling recently won the 2025 Three Minute Thesis competition on campus, where she had to explain her research in language the general public would understand in three minutes.

One fact Thiel called “absolutely alarming” is that mortality related to uterine cancer is worse today than in the 1970s.

“I personally want women to know that abnormal bleeding that is not typical is one of the earliest signs of uterine cancer, and just go to the doctor and get checked for it, because early detection really is important,” Thiel said.